Historic Highway SR 11

Historic Highway SR 11, Chuckanut Drive, MP 9 to MP 19.92

Skagit and Whatcom Counties

Significance

Renowned for its scenic beauty, the segment of SR 11 known as Chuckanut Drive is NRHP eligible per Criterion A for its association with early highway construction in Washington, and per Criterion C for its integrity of design, location, workmanship, feeling and setting. Integral to the setting on the steep mountainside above Samish and Chuckanut Bays, the design of Chuckanut Drive makes it the premier historic scenic highway in the state. The segment includes three NRHP eligible bridges: Blanchard Bridge 11/7, Oyster Creek Bridge 11/8 and Padden Creek Bridge 11/102.

Historical Background

In 1896, funding from the State of Washington and Skagit County supported construction of a road along the shoreline below the present highway. Known as the Old Blanchard Road, it served as the first road connecting Whatcom and Skagit counties (earlier travel being by boat or horseback). Skagit County commissioners sold three miles of that road to the Great Northern Railway for its “Chuckanut Cutoff,” built in 1901. As auto and bicycle touring increased in popularity, Cyrus Gates and C.X. Larrabee, business partners in northwest Washington, envisioned a scenic roadway overlooking Samish and Chuckanut Bays and Strait of Juan de Fuca. They helped influence the Washington Legislature to appropriate $25,000 in 1909 for construction of a road on the flanks of Chuckanut Mountain. In 1910, when the state built a labor camp at the mouth of Oyster Creek, convicts began building the road on a route suggested by Gates and Larrabee. Slowed by the challenging terrain, the convicts completed only 4,000 feet of roadway from Blanchard to Oyster Creek. Critics accused the Highway Department of “bungling” and wasting public money by building less than a mile of the 5.5 miles of roadway intended by the 1909 appropriation. Determined to see the plan through, the Department contracted with Quigg Construction Company in 1913 to build an additional four miles of roadway. Failure to prevent debris from falling on the railroad directly below the highway resulted in the railroad suing the state and the contract being rescinded. State Highway Department work forces then finished the remainder of the road. By 1916, when Chuckanut Drive was finally opened to automobile traffic, approximately $135,000 had been expended. In 1920, the City of Bellingham paved a section of the road approaching its north end to Inspiration Point near the road’s 1,460-foot summit. With federal aid, the state extended the 20-foot-wide, 8-inch-deep concrete pavement three miles south from Inspiration Point at a cost of $35,000 per mile. Most of the road remained gravel until 1921, when two contracts resulted in paving nearly the entire route. By 1926, all but one mile of Chuckanut Drive between Oyster Creek and Blanchard had been paved in concrete. Other improvements included replacement of wooden bridges with concrete tee-beam structures at Oyster Creek, Blanchard, and Padden Creek in 1924, 1931 and 1932, respectively.

When completed in 1916, the road became part of Primary State Highway 1, known as the Pacific Highway 1 from the Canadian Border to San Diego in southern California. It was designated US Route 99 in 1926, but changed to US Route 99 Alternate in 1931 when an inland bypass was designated by the state as US 99. Highway renumbering changed the designation to State Route 11 in 1964. By this time, asphalt had replaced the original concrete paving.

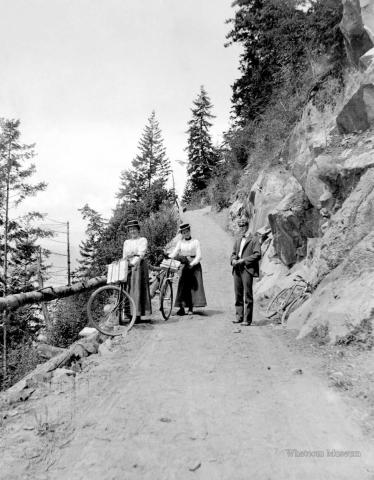

With enthusiasm typical of the early automobile era, the press touted Chuckanut Drive for being: 1) the first segment of the Pacific Highway between Canada and San Francisco to parallel the Pacific Ocean; 2) a critical link in the local economy connecting the agricultural Skagit Valley with shipping points on the shores of Whatcom County, and 3) a scenic wonder providing “an incomparable panorama of Western Washington” (Seattle Sunday Times). Among the first travelers to appreciate the road’s scenery were bicycle riders, whose lobbying for a smooth-surface roadway helped bring about construction. Chuckanut Drive became a destination of automobile clubs and tourist buses. During Prohibition, the route was known as the “liquor runners’ road” for its frequent use by “rum runners” transporting illegal booze from Canada into the U.S.

Despite closures for rock fall removal and costly repairs of roadway failure due to landslides, Chuckanut Drive remains one of the most popular scenic highways in the state. In addition, it also serves as the only automobile access to Larrabee State Park. Originally known as Chuckanut State Park, the popular camping, hiking and boating destination began as a 20-acre donation of Frances Larrabee, Charles Larrabee’s widow. Making good on her husband’s promised donation, Mrs. Larrabee ensured creation of the first state park in Washington. In 1923, the State Parks Commission renamed it Larrabee State Park, which over the years has grown to its present 2,683 acres.

The historic highway segment includes three NRHP-eligible bridges: the Oyster Creek Bridge 11/8, the Blanchard Bridge 11/7 and the Padden Creek Bridge 11/102. Constructed in 1924, 1931 and 1932, respectively, the bridges evoke early automobile travel and concrete bridge building in the third and fourth decades of the twentieth century.

Oyster Creek Bridge: In 1924, the Washington State Highway Department awarded contract #825 to L.A. Farmer of Anacortes for $10,817.50 to build a concrete bridge to replace a temporary log bridge over Oyster Creek. Farmer built the 86-foot long, 26-foot wide concrete tee-beam structure on a 73 degree curve in the roadway. Work began on May 7, 1924, and was completed September 9, 1924. The bridge retains integrity of its character-defining features, including concrete baluster guardrails.

Blanchard Bridge: On February 5, 1931, the Washington State Highway Department awarded contract #1496 to Manson Construction and Engineering Company of Seattle for $10,817.50 for construction of the Blanchard Overhead Crossing of the Great Northern Railway. Work began in February and the 883- foot long concrete tee-beam bridge was opened to traffic on December 1, 1931. The bridge retains integrity of its character-defining features, including concrete baluster guardrails.

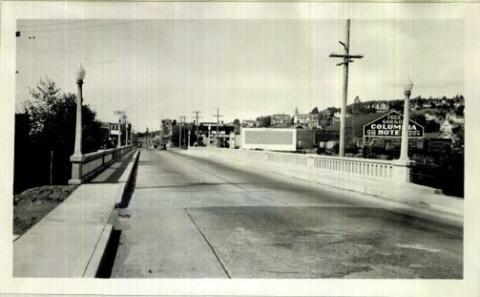

Padden Creek Bridge: On February 2, 1932, the Washington State Highway Department awarded contract #1620 to Lindstrom & Feigenson of Portland, Oregon, to build what was then called the 12th Street Bridge in Bellingham. Work began on the 539-foot long concrete tee-beam bridge on August 4th and was completed on August 20, 1932. The bridge retains excellent integrity of its character-defining features, including concrete baluster rails and what appear to be original glass lights on concrete standards.

Description

The NRHP-eligible segment of highway begins on its south end at MP 9 at the intersection of Legg Road. Its northern termination is in the town of Fairhaven at the north end of Padden Creek Bridge at MP 19.92. The nearly 11-mile segment typifies a historic highway in Washington: a relatively narrow two- lane roadway with little or no shoulders, occasional widening, restricted sight distance, limited or non-existent clear zones, at-grade driveway and rural road crossings, vehicle weight restrictions, commercial truck and bus travel prohibitions and severely reduced speed limits.

Chuckanut Drive would today be recognizable to anyone who had read the newspaper in 1916: “The roadbed is fully twenty feet wide in the narrowest places and where necessary retaining walls of concrete and stone insure the permanency. Heavy wooden guards make the passing of all vehicles absolutely safe” (Seattle Sunday Times). Although widened slightly in places, with additional pullouts and improved traffic barriers, the highway is essentially unchanged since its construction. Catastrophic events, such as rock and mudslides, have been repaired, resulting in modern retaining walls that have stabilized the roadway. However, the highway’s precarious location has been retained. Original stone and mortar walls, built more for decoration than safety, have been rebuilt at scenic pullouts. Some original stone and mortar walls have been retained along the roadway, such as the low wall at MP 9.95.

Interpretive signs have been installed at pullouts recounting the history of Chuckanut Drive (MP 12.45) and oyster beds (MP 11.5) in the vicinity of Oyster Creek.

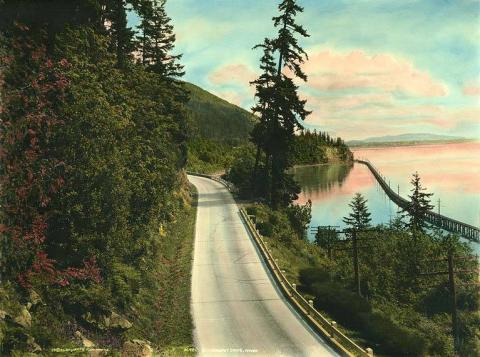

1926 postcard view of Chuckanut Drive, showing the railroad trestle crossing the Bay.

Bicyclists on Chuckanut Drive, ca. 1916. Courtesy Whatcom Museum, image #1996.10.3512.

Inspiration Point on Chuckanut Drive, ca. 1920. Courtesy Whatcom Museum, image #X.3219.4791.

Overlook at MP 12.45 with rock wall, 2017.

Chuckanut Drive near south end of segment, ca. 1916. Courtesy Whatcom Museum, image #1996.10.2516.

Chuckanut Drive and parking lot of the Chuckanut Manor Restaurant near the south end of the NRHP- eligible highway segment, 2017. View to north.

Chuckanut Drive at MP 14, 2017. View to south.

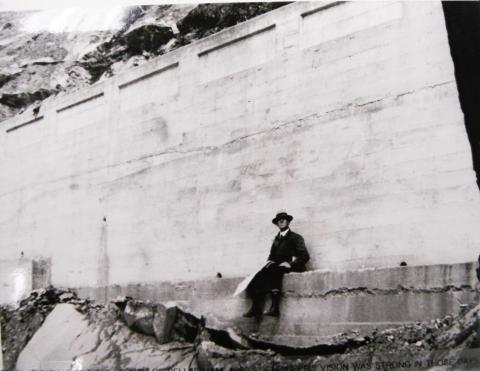

Concrete retaining wall and reportedly an engineer working on road construction, ca. 1916.

Repairing failed concrete retaining wall on Chuckanut Drive. Courtesy Whatcom Museum, image #1995.1.30350.

Concrete wall and railing on Chuckanut Drive, 2016.

Blanchard Bridge #11/7 near south end of NRHP-eligible highway segment. View to north.

Oyster Creek Bridge, 1925. Courtesy Whatcom Museum, image #1968.32.114.

Padden Creek Bridge, south edge of Fairhaven, Final Record Notes, WSDOT Engineering Records, 1932.

Slow down – lives are on the line.

In 2023, speeding continued to be a top reason for work zone crashes.

Even one life lost is too many.

Fatal work zone crashes doubled in 2023 - Washington had 10 fatal work zone crashes on state roads.

It's in EVERYONE’S best interest.

95% of people hurt in work zones are drivers, their passengers or passing pedestrians, not just our road crews.